In the modern digital landscape, data is the most valuable and vulnerable asset. From financial transactions and personal health records to intellectual property and national security secrets, the volume and sensitivity of information transmitted and stored electronically are immense. This critical reliance on digital data demands a corresponding level of protection against eavesdropping, unauthorized access, and theft. Encryption is the mathematical foundation of this protection, serving as the essential tool that transforms readable information into an unreadable, coded format, ensuring confidentiality and integrity. It is the invisible shield that secures everything from cloud storage to instant messaging and e-commerce.

This comprehensive guide delves into the intricate workings of data encryption, moving beyond simple definitions to explore the complex cryptographic algorithms and key management systems that power global security. We will dissect the two major categories of modern encryption—Symmetric and Asymmetric—analyze the role of hash functions, and detail how Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) validates trust in a world without physical boundaries. Understanding how encryption really works is crucial for anyone navigating the complexities of digital commerce, cloud computing, and cybersecurity.

1. The Core Concepts of Cryptography

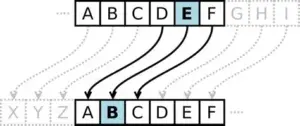

Encryption is a branch of cryptography, the science of secure communication in the presence of adversarial third parties. To understand encryption, one must grasp its foundational terminology and goals.

A. Plaintext and Ciphertext

-

Plaintext: This is the original, readable message or data. It is the information in its understandable form, ready to be processed or transmitted.

-

Ciphertext: This is the encrypted, scrambled, or coded version of the plaintext. It is unreadable without the correct decryption key.

B. Encryption and Decryption

-

Encryption: The process of converting plaintext into ciphertext using a specific algorithm (the cipher) and a cryptographic key.

-

Decryption: The reverse process of converting the ciphertext back into the original plaintext using the correct key and the corresponding algorithm.

C. The Cryptographic Key

The key is the most vital component of the encryption process. It is a piece of information (a string of bits) that determines the output of the encryption algorithm. The security of the entire encryption scheme hinges on the secrecy and complexity of the key. Modern cryptographic systems rely on the Kerckhoffs’s Principle, which states that a cryptosystem should be secure even if everything about the system, except the key, is public knowledge.

D. Core Security Goals

Encryption is primarily used to achieve several fundamental security objectives:

-

Confidentiality: Ensuring that data is hidden from unauthorized users (e.g., securing an email so only the intended recipient can read it).

-

Integrity: Ensuring that data has not been tampered with or altered during transit or storage.

-

Authentication: Verifying the identity of the user or system that created or sent the data (e.g., digital signatures).

-

Non-Repudiation: Preventing the sender from later denying they sent the message.

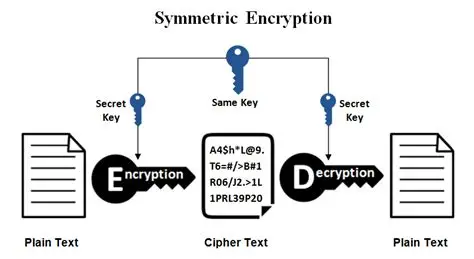

2. Symmetric-Key Encryption: The Shared Secret

Symmetric encryption, also known as secret-key cryptography, is the oldest and fastest form of encryption. It relies on a single, shared secret key for both encryption and decryption.

A. Operational Mechanics

In a symmetric scheme, two parties (Alice and Bob) must agree upon and securely exchange the same secret key before communication can begin.

-

Encryption Formula: Ek(P)=C (Encrypting Plaintext P with Key K results in Ciphertext C)

-

Decryption Formula: Dk(C)=P (Decrypting Ciphertext C with the same Key K results in Plaintext P)

B. Performance and Use Cases

Symmetric algorithms are generally computationally fast and highly efficient, making them ideal for encrypting large volumes of data.

-

Stream Encryption: Encrypting large files, database contents, and network traffic (e.g., bulk data encryption in a Virtual Private Network or encrypting a hard drive).

-

Common Algorithms:

-

Advanced Encryption Standard (AES): The most widely used symmetric cipher, adopted by the U.S. government and banks globally. AES supports key sizes of 128, 192, and 256 bits, offering extremely strong security.

-

ChaCha20: A fast, modern stream cipher often used in mobile applications and protocols like TLS.

-

C. The Key Distribution Problem

The primary weakness of symmetric encryption is the Key Distribution Problem. How do two parties securely exchange the single secret key over an unsecure channel (like the internet) without an eavesdropper intercepting it? This crucial problem is solved by leveraging asymmetric encryption.

3. Asymmetric-Key Encryption: The Key Pair

Asymmetric encryption, also known as Public-Key Cryptography (PKC), uses a pair of mathematically linked keys: a public key and a private key. This innovation fundamentally solved the key distribution problem.

A. Key Pair Mechanics

Each user (say, Alice) generates a unique pair of keys:

-

Public Key: This key can be freely shared with anyone. It is used to encrypt messages intended for Alice and to verify digital signatures created by Alice.

-

Private Key: This key must be kept secret and secure by Alice. It is used to decrypt messages encrypted with Alice’s public key and to create digital signatures.

B. Encryption and Decryption Flow

The process uses the public key for encryption and the private key for decryption.

-

Encryption: If Bob wants to send a secret message to Alice, Bob uses Alice’s Public Key to encrypt the message.

-

Decryption: Only Alice’s Private Key can decrypt the ciphertext back into the original plaintext. If an eavesdropper intercepts the ciphertext, they cannot decrypt it without Alice’s Private Key.

C. Performance and Use Cases

Asymmetric algorithms are computationally intensive and significantly slower than symmetric algorithms. They are typically reserved for specific tasks:

-

Secure Key Exchange: The most vital use is to securely exchange the Symmetric Key (a small, temporary piece of data) that will then be used for the bulk of the communication.

-

Digital Signatures: Used to verify the authenticity and integrity of a document or sender.

-

Common Algorithms:

-

RSA: One of the oldest and most trusted asymmetric algorithms, still widely used for digital signatures and key exchange.

-

Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC): A modern, highly efficient alternative to RSA that provides the same level of security with significantly shorter key lengths.

-

4. Hybrid Cryptography: Combining the Best of Both Worlds

Virtually all modern secure protocols (like TLS/SSL for websites) use a hybrid cryptosystem to maximize both speed and security.

A. The Hybrid Process

The hybrid approach uses asymmetric encryption to solve the key distribution problem and symmetric encryption to handle the efficient transfer of large data.

-

A. Setup: Alice and Bob agree to communicate.

-

B. Key Exchange (Asymmetric): Bob randomly generates a session key (a temporary symmetric key) for the communication. Bob encrypts this session key using Alice’s Public Key.

-

C. Key Decryption: Bob sends the encrypted session key to Alice. Alice uses her Private Key to decrypt and retrieve the symmetric session key.

-

D. Bulk Data Transfer (Symmetric): Both Alice and Bob now share the secret session key. All subsequent large data packets are encrypted and decrypted quickly using the fast Symmetric Algorithm (AES) and the shared session key.

B. Session Key Security

This approach ensures that even if an eavesdropper intercepts the entire communication, the temporary symmetric session key (used for bulk data) is protected by the strong asymmetric encryption layer. The session key is destroyed after the communication ends, further limiting its exposure.

5. Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) and Trust

For asymmetric encryption to function securely in public, there must be a way to verify that a public key truly belongs to the entity it claims to represent (e.g., verifying a website’s public key actually belongs to the bank). This is the role of Public Key Infrastructure (PKI).

A. Digital Certificates

A Digital Certificate is the cornerstone of PKI. It is an electronic document that links a public key to an entity’s identity (like a website domain or an individual user).

-

Contents: The certificate contains the entity’s public key, the entity’s identification information, and, most importantly, a digital signature from a trusted third party.

B. Certificate Authorities (CAs)

Certificate Authorities (CAs) are trusted organizations that issue and manage digital certificates.

-

The Role of Trust: When a website owner requests a certificate, the CA verifies the owner’s identity (e.g., confirms domain ownership) and then uses its own highly protected Private Key to digitally sign the certificate.

-

Verification: When a user’s web browser connects to the site, it verifies the CA’s signature using the CA’s well-known Public Key. If the signature is valid, the browser trusts that the website’s public key is authentic.

C. Certificate Revocation

PKI also manages the revocation of certificates if a private key is compromised or the certificate holder is no longer trusted. This is done via services like the Certificate Revocation List (CRL) or Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP).

6. Hashing Functions and Data Integrity

While encryption ensures confidentiality, hashing functions are the primary tool used to guarantee data integrity—that the data has not been altered.

A. Hashing Mechanics

A hash function is a one-way mathematical algorithm that takes an input (data of any size) and produces a fixed-size, unique string of characters called a hash value or digest.

-

One-Way Street: The process is irreversible; it is computationally infeasible to reconstruct the original data from the hash value.

-

Determinism: The same input always produces the exact same hash output.

-

Collision Resistance: A tiny change in the input data must produce a drastically different hash output. It must also be computationally infeasible to find two different inputs that produce the same output (a hash collision).

B. Use Cases for Integrity

Hashing is used extensively to verify data integrity:

-

File Verification: When downloading a large file, the provider publishes the file’s hash digest. The user calculates the hash of the downloaded file. If the two hashes match, the user is confident the file was not corrupted or tampered with during the transfer.

-

Password Storage: Systems do not store users’ passwords; they store the hash of the password. When a user tries to log in, the system hashes the provided password and compares the result to the stored hash. If they match, the identity is verified without ever exposing the original password.

-

Digital Signatures: When creating a digital signature, the sender first hashes the document, and then encrypts only the small hash value using their Private Key. This signature guarantees that the document has not been altered since it was signed.

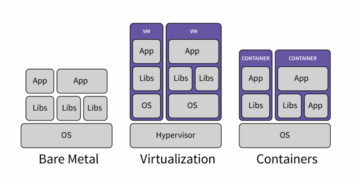

7. Encryption in Modern Cloud Systems

Encryption is mandatory in cloud architecture, covering data in three critical states: at rest, in transit, and in use.

A. Encryption at Rest

This protects data stored in cloud storage (databases, object storage, file systems).

-

Provider Managed Keys: The cloud provider handles the encryption and decryption using keys managed entirely by the service. This is the easiest method but offers the least control.

-

Customer Managed Keys (CMKs): The customer controls the encryption key’s lifecycle (creation, rotation, access control) using a Key Management Service (KMS). This provides greater control and auditability for compliance.

B. Encryption in Transit

This protects data moving over networks, both public and internal.

-

TLS/SSL: The ubiquitous protocol used to encrypt traffic between a user’s browser and a web server, utilizing the hybrid encryption model secured by PKI.

-

Internal Network Encryption: In highly secure cloud environments, microservices communicate using protocols like mTLS (mutual TLS) enforced by a service mesh, ensuring every internal packet is encrypted and mutually authenticated.

C. Encryption in Use (Confidential Computing)

This is the cutting edge of security, protecting data while it is being actively processed by the CPU and memory.

-

Homomorphic Encryption: A complex method that allows computation to be performed directly on ciphertext, yielding an encrypted result that, when decrypted, matches the result of computation performed on the plaintext.

-

Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs): Hardware-based enclaves that create a secure, isolated region of memory and CPU where code and data can be processed without exposure, even to the host operating system or administrator.

8. Cryptographic Key Management Lifecycle

The effectiveness of encryption ultimately depends on the security of the key management process—the control, storage, and lifecycle of the encryption keys.

A. Key Generation and Strength

Keys must be generated using true random number generators to ensure they are unpredictable. Key strength is measured by its length:

-

128-bit Symmetric Key (AES): Offers strong security; the number of possible keys is 2128.

-

2048-bit Asymmetric Key (RSA): Provides an equivalent level of security but requires a longer key length due to the nature of the factoring problem upon which RSA is based.

B. Key Storage and Rotation

Keys should never be stored in plain text and should reside in dedicated, hardened systems.

-

Hardware Security Modules (HSMs): Dedicated, tamper-resistant physical devices designed specifically to store cryptographic keys securely and perform encryption operations. Cloud KMS services are often backed by HSMs.

-

Key Rotation: Keys should be regularly rotated (e.g., annually) to limit the amount of data encrypted by a single key, minimizing the potential damage if that key were ever compromised.

C. Key Destruction

When a key is retired or a data set is permanently deleted, the encryption key associated with it must be securely and permanently destroyed to ensure the data becomes permanently inaccessible.

Conclusion: Encryption as a Digital Prerequisite

Data encryption is far more than a technical feature; it is a fundamental prerequisite for participation in the digital world. By leveraging the mathematical elegance of Symmetric-Key (AES) for speed and Asymmetric-Key (RSA/ECC) for secure key exchange, modern cryptography creates the resilient security protocols that underpin all digital communication.

The integrity of this system rests on robust Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) to verify trust and powerful Hashing Functions to ensure data integrity. As computing evolves into the cloud and to the edge, the focus is expanding from securing data at rest and in transit to protecting data in use through technologies like confidential computing. Mastering the principles of encryption and key management is the cornerstone of building secure, trustworthy, and compliant digital systems for the future. Encryption is the language of digital trust.